Emphysema is a debilitating lung condition that leaves patients feeling breathless and anxious.

On face value you’d think lack of air is the problem – but in reality, emphysema-damaged lungs retain too much air.

That’s why one of the approaches to treat emphysema patients is to reduce lung volume.

Soon more patients may be able to access this kind of treatment thanks to a new clinical trial being held at the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) and other sites across Australia.

Professor Phan Tien Nguyen is head of unit in the Department of Thoracic Medicine at the RAH, Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN) and one of the doctors involved in the trial.

“In emphysema patients we see two main issues that result from damage to lung cells,” says Professor Nguyen.

“People struggle to get enough oxygen, reducing their ability to do normal daily activities.”

“On top of that, the lung tissue that is left forms pocket-like structures, in which air becomes trapped.”

Trapped air means lungs become hyperinflated.

“The lungs become too big for the chest cavity, and don’t have enough room to move during breathing,” Professor Phan says.

The feeling of having lungs too big for their chest is one of the factors that creates anxiety in emphysema patients.

Different approaches to treat emphysema

Emphysema is not reversible, so management is all about reducing symptoms and preventing further progression.

Smoking is the leading cause of emphysema, so the primary health advice is to support patients to stop smoking.

Other medications can help too. For example, inhalers may relax the airways to allow increased delivery of oxygen, and antibiotics and steroids help treat infection and reduce inflammation.

A more permanent approach involves reducing lung volume.

“In the past, trials showed that operations to remove part of a damaged lung could be effective in helping patients feel better,” says Professor Phan.

“While that was true for some patients, the operation can be quite risky.”

More recently, a different approach to lowering lung volume was trialled: a valve that is inserted into the lung and allows air to move back out of hyperinflated lung tissue but no new air to come in.

“Our research shows these one-way valves can improve lung function, exercise capacity and quality of life for some patients with emphysema,” Professor Phan says.

“AT CALHN this procedure is one of the standard care offerings for qualifying patients.”

New clinical trial

There are some emphysema patients for whom one-way valves are not currently suitable.

In these people, lung damage has progressed to the extent that air flows between holes in neighbouring areas of lung that would not normally be connected.

A new clinical trial is investigating whether such holes can be safely and effectively repaired to an extent that one-way valves can be used.

“This is an international trial taking place in Australia, Europe and United States,” says Professor Phan.

“The Royal Adelaide Hospital is one of three Australian trial sites for this approach. Along with my co-investigators, Professor Hubertus Jersmann and Associate Professor Arash Badiei, we are very excited to offer this to eligible patients in SA.”

Referring clinicians can visit the RAH Clinical Trials Centre webpage or contact RAHRespiratoryClinicalTrialsUnit@sa.gov.au to learn more.

Read the research

Professor Phan’s research documenting the use of endobronchial valves in patients with emphysema was published with colleagues from the Adelaide Medical School, University of Adelaide, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, and SA Medical Imaging.

It is freely available to read at the Internal Medical Journal: A 6-year experience of Zephyr endobronchial valves for severe emphysema in an Australian single-centre cohort.

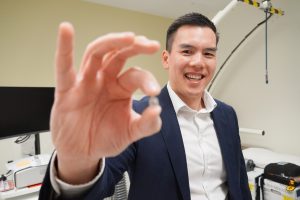

Lead image shows Professor Phan with a 3D-printed model of lung airways used for doctor training.